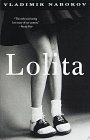

Nabokov, Lolita (Part Two)

Lolita on Page and Screen

In class tomorrow, we'll be looking at a few scenes from the two movies

(each notorious in its own right) that have been made of Lolita:

Stanley

Kubrick's 1962 film and Adrian

Lyne's 1997 version, as well as (I hope) devoting a bit of time

to the further discussion of the plot, suspense, romantic and ludic

elements of the novel. I'll be interested to hear from you (online or

in class) about how you're enjoying Part Two (and why). N.B.: I will

also be asking you to fill out class evaluations tomorrow, so—in

the interests of the continued health of the Core Curriculum—please

make every effort to be in class. Your comments on the written part

of the evaluation are read carefully by the Director of the Core Curriculum,

although I can't vouch for the bubble-form portion (which goes straight

to the Deans).

Study Questions (optional)

The following study questions are largely taken from a Random

House website devoted to Lolita, with my own additions, emendations,

and general editing. Normally I don't find other people's study questions

very useful—they often seem pitched rather below your level—but

these are quite good, I think. I am still trying to preserve the mystery

of "what happens at the end" for those of you who haven't

read all the way through yet, so I've left a few of the Random House

questions out—and in your online discussion, those of you who have

read the book before, please try to limit yourself to discussing the

plot through p.247 only!

-

Humbert's confession is written [as all of you have noted] in an extraordinary language. It is by turns colloquial and archaic, erudite and stilted, florid and sardonic. It is studded with French expressions, puns in several other languages, and allusions to authors from Petrarch to Joyce. Is this language merely an extension of Nabokov's own—which the critic Michael Wood describes as "a fabulous, freaky, singing, acrobatic, unheard-of English"[1]—or is Humbert's language appropriate to his circumstances and motives? In what way does it obfuscate as much as it reveals? And if Humbert's prose is indeed a veil, at what points is this veil lifted and what do we glimpse behind it?

-

Humbert attributes his "nympholepsy" to his tragically aborted childhood romance with Annabel Leigh. How far can we trust this explanation? How do we reconcile Humbert's reliance on the Freudian theory of psychic trauma with his corrosive disdain for psychiatrists?

-

In the early stages of his obsession Humbert sees Lolita merely as a new incarnation of Annabel, even making love to her on different beaches as he tries to symbolically consummate his earlier passion. In what other ways does Humbert remain a prisoner of the past? Does he ever succeed in escaping it? What is Lolita's relationship to her own past, and how does it compare to Humbert's?

-

How does Humbert's marriage to Valeria foreshadow his relationships with both Charlotte and Lolita? How does the revelation of Valeria's infidelity prepare us for Lolita's? Why does Humbert respond so differently to these betrayals?

-

Humbert Humbert is an émigré. Not only has he left Europe for America, but in the course of Lolita he becomes an erotic refugee, fleeing the stability of Ramsdale and Beardsley for a life in motel rooms and highway rest stops. How does this fact shape his responses to his environment (including other characters) and its responses to him? To what extent is the America of Lolita an exile's America? What is his America like? Is it possible to see Lolita as Nabokov's veiled meditation on his own exile? Does the novel change your awareness of your own perspective on America?

-

We also learn that Humbert is mad—mad enough, at least, to have been committed to several mental institutions, where he took great pleasure in misleading his psychiatrists. How does this colour our reception of his narrative? How reliable do you find him, as a narrator?

-

What makes Charlotte Haze so repugnant to Humbert? Does the author appear to share Humbert's antagonism? Does he ever seem to criticize it?

-

To describe Lolita and other alluring young girls, Humbert coins the word "nymphet." The word has two derivations: the first from the Greek and Roman nature spirits, who were usually pictured as beautiful maidens dwelling in mountains, waters, and forests; the second from the entomologist's term for the young of an insect undergoing incomplete metamorphosis. Note the book's numerous allusions to fairy tales and spells; the proliferation of names like "Elphinstone," "Pisky," and "The Enchanted Hunters," as well as Humbert's repeated sightings of moths and butterflies. Also note that Nabokov was a passionate lepidopterist, who identified and named at least one new species of butterfly. How does the character of Lolita combine mythology and entomology? In what ways does Lolita resemble both an elf and an insect? What are some of this novel's themes of enchantment and metamorphosis as they apply both to Lolita and Humbert, and perhaps to the reader as well?

-

Before Humbert actually beds his nymphet, there is an extraordinary scene, at once rhapsodic, repulsive, and hilarious, in which Humbert excites himself to sexual climax while a (presumably) unaware Lolita wriggles in his lap. How is this scene representative of their ensuing relationship? What is the meaning of the sentence "Lolita had been safely solipsized" [p. 60], "solipsism" being the epistemological theory that the self is the sole arbiter of "reality"?

-

Does Humbert "really love" Lolita? Does he ever perceive her as a separate being? Is the reader ever permitted to see her in ways that Humbert can/does not?

-

Humbert meets Lolita while she resides at 342 Lawn Street, seduces her in room 342 of The Enchanted Hunters, and in one year on the road the two of them check into 342 motels. These are just a few of the coincidences that make Lolita so profoundly unsettling. Why might Nabokov deploy coincidence so liberally in this book? Does he use it as a convenient way of advancing plot or in order to call the entire notion of a "realistic" narrative into question? How do Nabokov's games of coincidence tie in with his use of literary allusion and self-reference ?

-

A related questions: Having plotted Charlotte's murder and failed to carry it out, Humbert is rid of her by means of a bizarre, and bizarrely fortuitous, accident. Is this the only time that fate makes a spectacular intrusion on Humbert's behalf? Are there occasions when fate conspires to thwart him? Is the fate that operates in this novel—a fate so preposterously hyperactive that Humbert gives it a name—actually an extension of Humbert's will, perhaps of his unconscious will? Is Humbert in a sense guilty of Charlotte's death? Discuss the broader questions of fate and culpability as they resonate throughout the novel [in a Dostoevskian manner that many of you have already commented on...]..

-

If we accept Humbert at his word, Lolita initiates their first sexual encounter, seducing him after he has failed at violating her in her sleep. Yet later Humbert admits that Lolita sobbed in the night—"every night, every night—the moment I feigned sleep" [p. 176]. Should we read this reversal psychologically: that what began as a game for Lolita has now become a terrible and inescapable reality? Or has Humbert been lying to us from the first? What is the true nature of the crimes committed against Lolita? Does Humbert ever genuinely repent them, or is even his remorse a sham? Does Lolita forgive Humbert or only forget him?

-

Humbert is not only Lolita's debaucher but her stepfather and, after Charlotte's death, the closest thing she has to a parent. What kind of parent is he? How different is his style of parenting from Charlotte's?

-

As previously mentioned, Lolita abounds with games: the games Humbert plays with his psychiatrists, his games of chess with Gaston Godin, the transcontinental games of tag and hide-and-go-seek that "Trapp" plays with Humbert, and (still to come) the slapstick game of the murder. There is Humbert's poignant outburst, "I have only words to play with!" [p. 32]. In what way does this novel itself resemble a vast and intricate game, a game played with words? Is Nabokov playing with his readers or against them? How does such an interpretation alter your experience of Lolita? Do its game-like qualities detract from its emotional seriousness or actually heighten it?

[1]Michael Wood, The Magician's Doubts:

Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 1995, p. 5.

All the original content on these pages is licensed under a Creative

Commons License. Under this license, you may copy, alter, and redistribute any of the

original content on this site to your heart's content, provided that you

(a) credit me and/or link

back to this page; and (b) allow others to make similarly free use of any

work you create that is based on material from these pages. In other words,

share the love. You might also like to drop

me a line and let me know if you're using my stuff -- it's the nice

thing to do!

All the original content on these pages is licensed under a Creative

Commons License. Under this license, you may copy, alter, and redistribute any of the

original content on this site to your heart's content, provided that you

(a) credit me and/or link

back to this page; and (b) allow others to make similarly free use of any

work you create that is based on material from these pages. In other words,

share the love. You might also like to drop

me a line and let me know if you're using my stuff -- it's the nice

thing to do!